Rick Rubin and Pharrell - University of Science

I just wrote my Morning Pages and this thought came out on the back of thinking about Robin Hobb’s Farseer Trilogy:

“Imagine if I were to go further still and write about my relationship with The Chronicles of Thomas Covenant? Now THAT could be interesting to explore – analysing fantasy novels as a man seeking purpose and meaning. It gets back to my whole “Philosophy of Art” thing, about the space between the Artist and the Viewer. The Artist channels Source through his or her own filters, and the Viewer views through his or her own. It’s that space that’s so interesting to me: Pure Art.”

And then I turned on an interview with Pharrell and Rick Rubin, published on GQ’s channel in 2019. Pharrell is talking about the motions he goes through when he hears chords in an elevator that make him feel something.

Pharrell - There’s a whole university of science between what’s being played and what you’re hearing.

Rick – Yes. So you’re analysing yourself as much as the music.

Pharrell – Yeah. Cos if you don’t, then you don’t really… you’re not really getting the proper assessment of what’s happening, you know? If I’m hearing something, what I’m not paying attention to how I’m feeling, then for me, I don’t know what I’m listening to … that’s my way of, that’s my GPS, of understanding, that’s how I process things, is how I feel. And everything is catalogued by, and categorized by the feeling of it. If I can’t see how I feel about it, then I don’t even really know what it is. It’s just music.”

University of science. That’s quite an interesting way of putting it, although I’m not quite sure that I’d call it science. It’s more like openness, or empty space, or the universe, or God. That’s how I see it anyway. But the concept is the same, and I’d be a fool to ignore all these messages that I’m receiving on the back of Rick Rubin’s recently published book, The Creative Act: A Way of Being.

I just know I’m going to have to start trawling through my old emails and journal entries to find the piece of writing I mentioned in my Morning Pages, in which I talk about my philosophy of Art. It’s interesting to me that I came up with the philosophy while drunk - interesting and scary. It’s got me wondering whether I really should look back. Might it be triggering? If I follow the thread now, could it lead to the idea that alcohol really did open my mind and free me of fear? Is my sobriety strong enough to weather something like that? I think so. And I just know that I’m going to do it anyway, so why am I even wondering about it on these pages?

And now I’m listening to LL Cool J’s Rock the Bells and looking up ‘what is go-go?’. I’ve heard of go-go, but don’t know that I’ve ever really heard it before. I don’t think it was really a thing in the UK.

Rock the Bells has a real Licensed to Ill sound about it (Beastie Boys’ 1986 album, also produced by Rick Rubin).

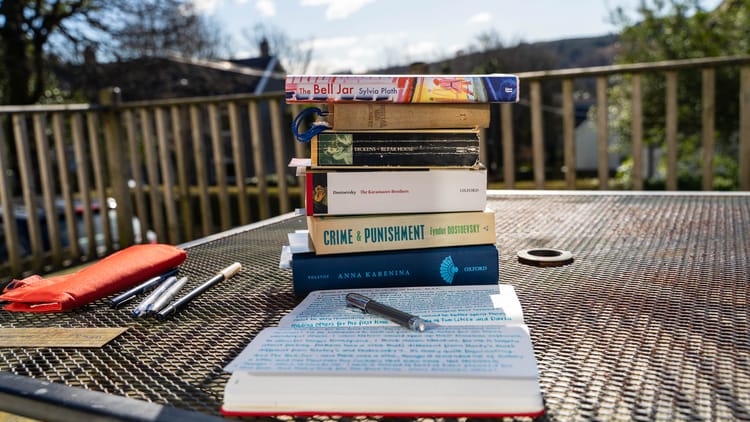

Hearing Pharrell talking about what it was like for him the first time he heard Rock the Bells reminds me a LOT of how I felt when I first heard Fight for your Right and my group of friends all got into Licensed to Ill. The whole VW badge thing! I have an entry in my diary about that, from 21 July 1987:

I got a VW badge yesterday. I was wearing it on my Adidas Colorado and the wifey in the bank asked me where I got it. She said she lived in Troon and I said I nicked it in Troon. She was a good laugh about it.

That music really stuck a chord with us. I was really too young for punk, so this was the first genre of music that spoke to me in such a profound way: street music made by irreverent young lads, rapping about alcohol and girls and parties. It was the ideal music to ride ramps to on our BMX bikes and skateboards.

When I was a 16-year-old recruit in the Royal Signals regiment in 1988, I remember reciting the whole of Paul Revere at the troop sergeant’s request during a corridor parade. I can’t remember if that culture was well known outside of my group of pals, but I suppose it must’ve been for that to have been a request, right?