Thank You to my Russian Teacher

This is the story of a man whom I never really thanked properly for what he did for me. It came up during a writing workshop about gratitude, hosted by Chris Schembra.

It’s quite early in the morning as I write. I woke up at the back of 6 after having had a dream about telling this story and I just knew I wasn’t going to get back to sleep. This story wants to be told, so I followed the wakeful muse and came through to sit at my computer. I’ve not even had coffee yet because I don’t want to wake the dogs up – they sleep in the kitchen. Also, the grinding of beans would probably wake up my wife and she’s been burning the usual December workload candle and is surviving on the bare minimum of sleep right now.

And so, to the man. His name is David Wolstencroft. He was a Russian teacher at the Army Apprentices’ College in Harrogate when I was there between June 1988 and August 1991. The AAC was a Royal Corps of Signals training camp for young soldiers between the ages of 16 and 19.

High School

Let’s set the scene.

I went to Prestwick Academy from 1983–1988. I didn’t do well there at all and came away at the end of five years with 3 SQA O’Grades and an SQA Higher in woodwork. These grades were all bare minimum passes and I only got the Higher because my birthday is in October and I wasn’t legally allowed to leave school at the end of fourth year. I begged, but the ‘no’ was firm.

My dad sowed the seed about joining the army while I was in my last year of high school. He’d served in the infantry when conscription was still a thing and ended up fighting in Korea at the age of 19. It’s surprising to me now as I write these words over 30 years later that that hadn’t put him off the idea of military service completely. He never spoke much about what he went through, but the stories that he did tell weren’t pretty.

Anyway, for reasons that were his own, he took me to visit his old training barracks at Berwick-on-Tweed. I don’t remember much about it other than reading Lord of the Rings in the back of the car.

Soon after that I visited the army careers office in Ayr and got some brochures, and it wasn’t long before I’d put in an application and was invited for a selection test.

The results of my selection test were good enough that I was able to apply for a trade rather than going into the infantry, so I picked the trade of radio telegraphist in the Royal Signals, simply because it was the only one on the list that had driving as part of the course. I knew nothing of communications or radios, but the selection test said I was qualified to apply and so that’s what I did.

Basic Training

I left for Harrogate in June 1988 and started six weeks’ basic training in intake 88B. It was a hot summer. One of the most enduring memories I have of that time is of how badly the standard-issue knitted-fibre shirts would rub the skin under my arms. We were actually the last intake to be issued those shirts, and not all of us got them. When we were issued them, we went through the stores in a single line based on surname. The KF shirts ran out after a certain letter around the middle of the alphabet and so if your surname started with around M or above, you got the new cotton shirts instead. I’m a Campbell, so yeah, raw oxters are what I remember most about basic training, them and wrapping our sheets and blankets into perfect rectangular bed blocks.

Funnily enough, the KF shirts became like a badge of superiority as they showed that you’d been in longer than anyone with the new cotton shirts. Even a few weeks gave you superiority at the college. Anyone below you would be forever a ‘rook’. Whatever. I got rid of mine as soon as I could, nasty things that they were!

During basic training, we were all required to sit a language aptitude test. I suppose that the corps was short of Russian linguists and the order had come down from on high to find some. I had no idea that I had an aptitude for languages, given that I’d dropped high school French at the earliest possible opportunity. The test involved reading a list of words in Kurdish with their English equivalents and then turning the paper over and writing down as many as you could remember. It wasn’t much of a test for language aptitude; more a simple memory test really.

I scored well and was soon offered the ‘opportunity’ to switch trades to Electronic Warfare Operator. It sounded sexy, but I declined. They couldn’t tell me much about what the job entailed because it was an intelligence trade. All they could tell me was that I’d be learning Russian intensively for two years, then learning the actual job at a more secure training base if I got through the two years at Harrogate. Eh, no thanks.

I went off on my four weeks’ summer leave after basic training with the belief that I was going back in September to start my radio telegraphist training.

While I was home, my dad—a self-employed joiner—just happened to be doing a job for an ex-Signals NCO who knew a thing or two about the intelligence trades. I wish I’d made notes of this in my diary as I could be misremembering it, but in my head I remember being talked round and agreeing to switching trades to EWOP. I also remember getting back to Harrogate to discover that they’d already switched me anyway. That’s the army for you!

Not only did this mean having to switch squadrons - not an easy thing to do as squadron loyalty gets hammered into you during those first six weeks, but, even worse, I’d have to be backsquadded. Remember I said how important even a few weeks could be at the college? Now I was back-squadded to 88C, the September intake. The horror!

Intake 88C included some EWOPs so the college decided that the 88B switchers would mark time until 88C finished their basic training and started trade training. That marking time basically meant going to trade training with the Special Telegraphists, or ‘Spec Ops’, the other intelligence trade that was trained at the college. So that’s how I learned morse code, but, more importantly, it gave me a glimpse into what the army could actually be like as a regular.

As a recruit and an early apprentice, you get screamed and shouted at a lot and made to feel like you’re the lowest of the low and not worth the shit on even a lance jack’s shoe (the lowest NCO rank). In the secure training wing where the Spec Ops went for trade training, we were treated like actual people. That helped me a lot at the age of 16 to feel like I hadn’t made a huge mistake in signing up.

Russian classes

We started our Russian classes around October 1988. David Wolstencroft was my teacher. I did a year of classes with David as part of intake 88C and then had a climbing accident in July 1989 while training in the Lake District. I was in hospital and recovery for over a year and recommenced classes with intake 89B in September 1990. It was a life-changing event, as you’ll imagine, and my future in the Signals was no longer secure.

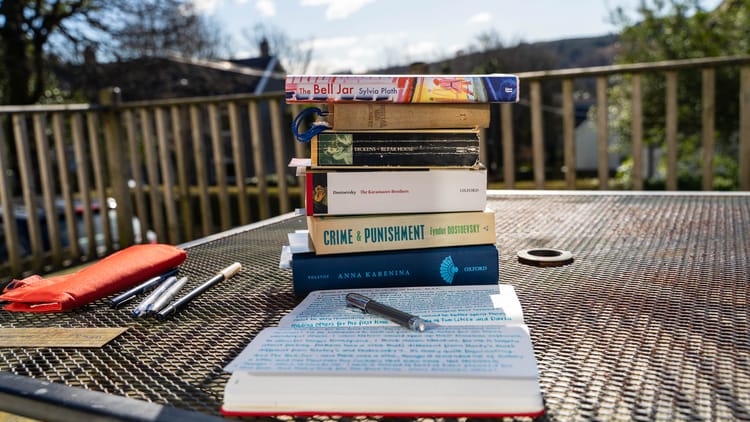

David’s teaching methods suited me and I’d never experienced that before. The first word we learned was the Russian word for ‘rocket’. Funny how I remember that. David was working from a set syllabus of military Russian that I imagine he’d been teaching for many years. I kind of wish I’d kept those text books, but they got chucked out somewhere along the line. I remember how he taught us verb declensions, using a method that I’ve never come across since. It clearly worked, because I took to it like I’d been born to it.

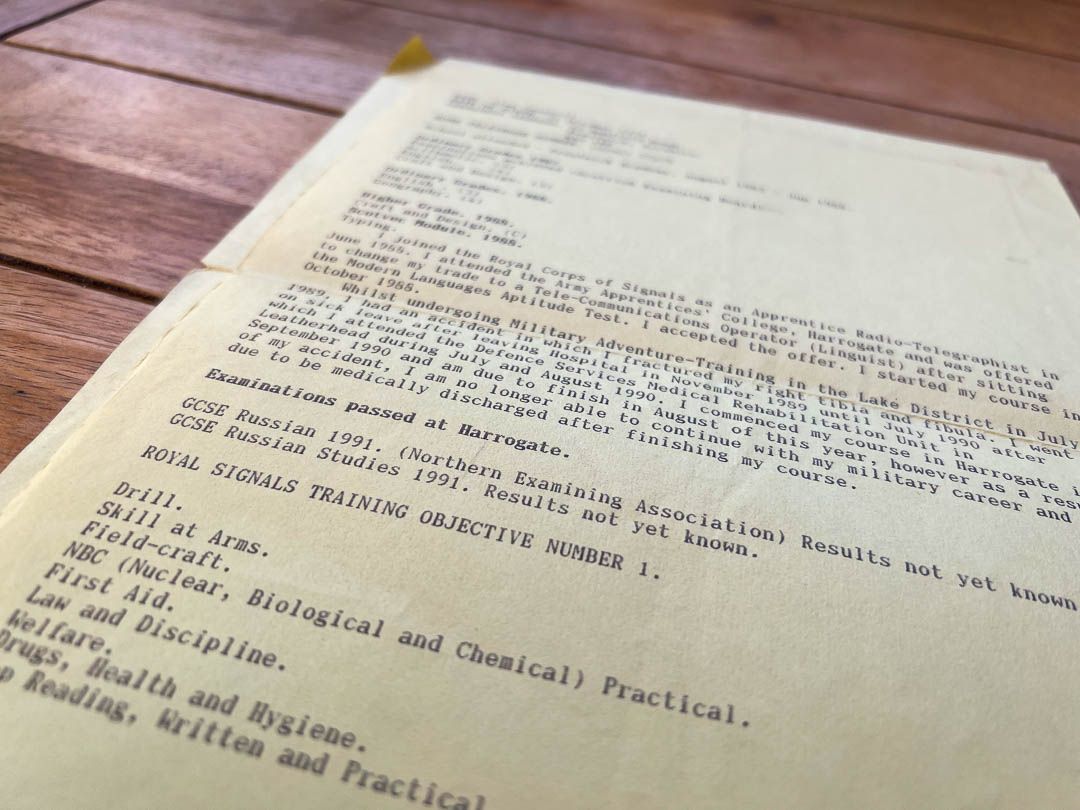

I don't remember that much about him, which is a real shame. All that comes to mind over 30 years later is his dry sense of humour. But it's really his kindness that I remember the most, when I was facing discharge and didn't know what to do with everything I had learned. I mean where does a 19-year-old Russian-speaking trainee intelligence officer go? Dave helped me not only with my applications to university but also to draft a full CV, something I'd never had to do before. I still have the typed-up yellow A4 sheets of paper with all my qualifications on it. It's a nice reminder of that time.

I sometimes wonder how much of my excelling at college is related to my Asperger’s and my level of emotional maturity just not being quite there when I was at high school. I see the same happening with my son right now; he’s 15. It gives me hope for him.

Grammar is something that I ‘see’, the logical connections of words and how they relate to form beauty. Russian is a wonderful language in terms of its grammar. It’s an inflected language, meaning that nouns’ endings change based on sentence structure and meaning. I found it to be really fun actually.

In David, I had a teacher who was able to get the best out of me and I really started to thrive. I became quite competitive in the class, with me and Kev Crabbe passing each other in the regular test results. He’d beat me, then I’d beat him. That competitive spirit helped to push me into excellence, too. This was something else I’d never experienced before.

My future

The college brass had assured me that my future in the Signals was secure, even if my medical condition after recovery wouldn’t quite meet the minimum requirements. I suppose that’s why they brought me back to Harrogate for my second year of trade training. But by the time I was approaching my tradeboard exams, I already knew that my medical discharge was looming.

This is when David really stepped up and helped me plan my future at university. It was a really difficult and uncertain time for me. I knew that I was going to graduate at the top of my class and then go straight back into the hospital for more surgery, but after that? David helped me draft letters to all the universities that had a Russian program and submit applications.

It ultimately came to naught because the universities weren’t going to accept military qualifications for entry and, as you already know, my high-school exam results just weren’t there.

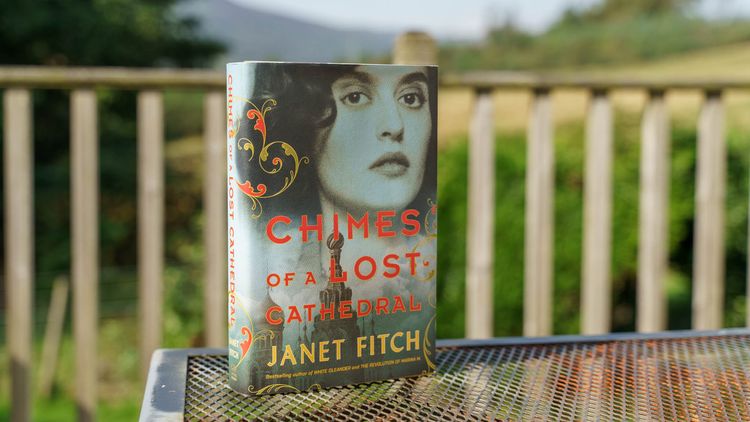

But the good work that David had done with me had shown me that I wasn’t the no-hoper that I’d always thought I was at school. He showed me that leaving the army wasn’t the end of a career before it had even started; it was the beginning of something else, and something good, something that I now had the confidence to reach out and take. He brought out the best in me and set me on a path that ultimately led to my becoming a Russian translator and working in Russia, Ukraine, Kazakhstan and Luxembourg. From a no-hoper at high school to a post-graduate with a Masters in Russian translation and interpreting, all thanks to the confidence that I got from David Wolstencroft at the Army Apprentices’ College in Harrogate.

David, thank you.